(The following interview was originally published on Reality Sandwich, and is exclusively about Tony’s third novel. A more general interview is available here.)

(The following interview was originally published on Reality Sandwich, and is exclusively about Tony’s third novel. A more general interview is available here.)

Spoiler Alert: In discussing his novel, Love and Other Pranks, the following interview necessarily reveals plot details. If you wish to be entirely surprised by the story, the reader is encouraged to enjoy the book first, and to read this interview as an Afterword.

Special thanks to performance philosopher and all-around renaissance artist Michael Garfield for his thoughtful questions.

Michael Garfield: Love and Other Pranks explores two parallel love stories set in different time periods. On the one side, it is a high-stakes caper set amidst the hedonism and hypocrisy of a New Age cult in modern-day San Francisco, while on the other side it is a mystical treasure hunt and swashbuckling pirate yarn set amidst the avarice and brutality of 18th-century Caribbean colonialism. Since it’s such a yin-yang of a book (or a Möbius strip), let’s start with a double question: How is love a form of piracy, or how is piracy a form of love?

Tony Vigorito: The pursuit of love—not just in the romantic sense, but also in the universal sense—is an act of rebellion of the highest order. In the same way that the archetypal pirate is both refugee from and revolutionary to their culture, love is a refuge from the sense of isolation and separateness that so agonizes the human experience – while also pointing the way toward a revolutionary expansion of human consciousness.

In his psychoanalytic classic, The Art of Loving, Erich Fromm describes love as the solution to the problem of human existence. And indeed, in its highest form, love is a treasure so tremendous that it has inspired seekers throughout human history. Some of them even found it, and echoes of the golden light they discovered within their very own hearts find their way back to us in the form of artistic expressions of every variety.

In its highest form, love is a treasure so tremendous that it has inspired seekers throughout human history. Ultimately, I think the pursuit of love represents an attempt to steal back our own heart, a heart that has been colonized and vastly diminished by social structures that imply that each of us is in this life alone and can therefore only count on one’s lonesome little self. Overcoming this “frozen lake of lovelessness”—as Dante termed the lowest level of his Inferno—requires a form of courage known only to pirates and other pranksters willing to explore outside the narrow confines of the social.

Where can I score some LP9? This fictional drug plays a significant role in Love and Other Pranks, so why invent a para-real drug for your novel on self-aware fictional characters within God’s story?

This is a stellar question on every level, Michael. I don’t know that I can capture every nuance of your question with my response, but let me try this:

In the first place, there is long tradition of inventing drugs in literature. Aldous Huxley invented soma for Brave New World, Philip K. Dick invented Substance D for A Scanner Darkly, Frank Herbert invented melange (or, the spice) for his Dune series, and—in film as well—the Wachowskis invented the red pill for The Matrix, just to name a prominent few. In fact, there are hundreds of such fictional drugs, and there’s an entire page on Wikipedia devoted to their catalogue.

Just like every human concept of the universe, it’s entirely make-believe, but the crucial difference is that fiction knows it’s make-believe.Second, the remarkable thing about fiction is that it is just that: Fiction. Just like every human concept of the universe, it’s entirely make-believe, but the crucial difference is that fiction knows it’s make-believe. Thereby, we can pretend anything at all into existence, liberating it from the physical limitations of, for example, “real-world” drugs, not to mention the cultural baggage that might surround them. I did this in my second novel, Nine Kinds of Naked, as well, where I invented a drug called m2 that people only encounter in their dreams.

And finally, since I am not aware of a piezoluminescent hyper-homeopathic amplifier molecule which might be the ultimate nootropic, might be a love potion, might be derived from the venom of a particular snake, might be the karmic antidote to nuclear weapons, might cure cancer, or might just be an elaborate urban legend, it became necessary to invent one.

There are a lot of amazing pranks and “life hacks” in this book. Quite literally, it is a trove of inspiration for the divergent minds among us who savor living in the blind spots and loopholes of our society. Without incriminating yourself, how much of this was drawn from personal experience? Some of these pranks seem too real to be made up, or even borrowed…

Con artist, heist, and caper stories occupy a prominent place in the American imagination. I think the stories fascinate us with their bravado and satisfy the merry prankster hidden within our soul, the part of us that knows that the whole of life is illusion—which doesn’t mean it isn’t real, by the way—it just means it can be whatever we want it to be.

Another reason we thrill to hear such stories is that we intuitively grasp how alienating our social structures are. A social system that guarantees nothing to its members—be it education, health care, or equality under the law—does nothing to motivate respect and conformity from its members. When someone finds a loophole in the lockdown, most of us only wish that we had found it first.A social system that guarantees nothing to its members does nothing to motivate respect and conformity from its members.

As to your direct question: Obviously, I haven’t participated in any armored truck and bank robberies, or even any of the number of lesser shenanigans the characters get into. Again, it’s fiction, inspired by research and a runaway imagination. That said, however, I do confess that I’ve stood in line at the bank and once or twice caught myself daydreaming about how I might rob the joint by applying social engineering techniques (some of which even made it into the story…). I don’t know what that says about me, other than that I’m honest in admitting to a common fantasy.

And while I’m being honest, I suppose it’s okay to humblebrag that the traveler’s check prank was inspired by a credit card scam that I and a couple of friends pulled off in college. But it was never illegal; it was just a loophole in their terms and conditions that we exploited to great effect. I regret to inform you that the door has now slammed on that loophole, but it was nonetheless satisfying to immortalize its heretofore unwritten history.

Also, the details on how to hack a key fob are entirely factual.

You really took a damning crack at narcissistic cult leaders in this book. Why did it feel like the right time to launch such a scathing satire of what seems to be a truly timeless issue?

At its most fundamental level, Love and Other Pranks is a story about malignant narcissism overthrown by an empowered femininity – and aided and abetted by an enlightened masculinity possessed of the courage to follow her lead. I myself was surprised at its sudden thematic pertinence to contemporary American politics, but then again, this is a story that has been simmering in the shadows of the American psyche for most of our history.

Narcissism will unravel our species if we do not learn to transcend it.Beyond that, the gurusional sociopaths who become narcissistic cult leaders are simply the worst expressions of dark potentials seething within us all. The truth may offend spiritual conceit, but narcissism is the human condition, and narcissism will unravel our species if we do not learn to transcend it.

Essentially, it works like this: We owe the genesis of our sense of self to others, and we derive our ongoing sense of worth and esteem from our estimations of how others perceive us. This dependency drives us to manage and even manipulate those perceptions, so that we may perceive ourselves according to our own identity ambitions: those social locations providing us with maximal access to material and non-material resources. All the confusions of history proceed once we identify with our social location rather than with our supreme self. It’s a labyrinthine sort of psyche in which we are lost, but it’s also a psyche that can liberate itself with love, which, incidentally, is the perfect opposite of narcissism.

Now that we’ve addressed the human characters, let’s address the animals. In a novel that challenges linear time about as much as is humanly possible, is Moby the parrot immortal?

Who can say? In the world building implicit in writing fiction, I’ve learned to make use of the undefined, by which I mean that it’s not necessary to spell out precisely how every piece of the story is happening. This is especially so around the edges of the story where details drift into surreality, leaving room for the reader to participate in the story by flexing their own interpretations – which is, after all, a primary goal of a successful life. The hugely-contradictory poet Ezra Pound once wrote that, “The book should be a ball of light in one’s hand,” and I entirely agree with this sentiment. By leaving some details up to the reader’s imagination, I hope to leave a door open in the mind in order that some light might get in and grant us all a blessed opportunity to stretch our souls outside the dictations of the social, or what Socrates once described as “a divine release of the soul from the yoke of custom and convention.”“The book should be a ball of light in one’s hand.” —Ezra Pound

Anyway, laying aside my artful evasions, Moby does seem to exist outside of the functions of everyday reality. It can only enrich our speculations by remembering that his name is short for Möbius.

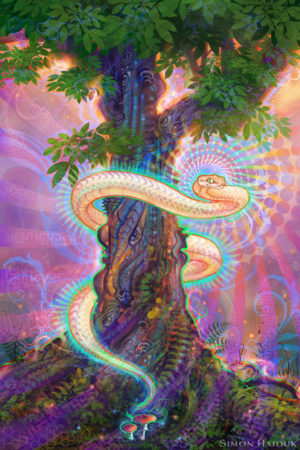

Let’s talk about the opalescent white snake that winds its way throughout this whole book – not exactly a typical portrayal of the devil. Was it just time to lay your own “flave” on this legendary character, or were there deeper motivations for it?

Let’s talk about the opalescent white snake that winds its way throughout this whole book – not exactly a typical portrayal of the devil. Was it just time to lay your own “flave” on this legendary character, or were there deeper motivations for it?

The devil? Is the opalescent white snake the devil? That’s certainly one reading—perhaps even an obvious one—but here again I went out of my way to leave it somewhat ambiguous. For example, the astute reader may notice that the serpent speaks only in the present tense – which was a defining trait of Billy Pronto, a character from my second novel, Nine Kinds of Naked, whose variable appearance was a projection of whomever he happened to interact. The serpent may just as easily be a trickster archetype, the serpent of kundalini, a miniature Leviathan, the Hindu deity Ahirbudhnya, the Aztec deity Quetzalcoatl, the Incan deity Sachamama, or maybe all these make-believe concepts are just different faces of the same underlying divinity.

With all of that said, however, I did find it useful to listen to The Rolling Stones’ Sympathy for the Devil at top volume before writing any of the opalescent white snake’s dialogue. So there’s that. And if the opalescent white snake was indeed the serpent of Eden—and I’m not necessarily admitting that it was—it’s worth remembering that in the Gnostic interpretation of Genesis, the serpent of Eden is considered the Serpent of Salvation, a messenger from the Supreme Being sent to liberate humanity from a profane material world imposed upon humanity by a false demiurge. It’s a fascinating—if heretical—interpretation, and one that writers like Philip K. Dick have been particularly keen on exploring.

An appropriately slippery “artful evasion” that also functions as an invitation into grinning paradox. Thank you! Seriously though, one of my favorite chapters was on the four pirates who died in battle. That elegiac section on four otherwise unnamed background characters did more to humanize and render transcendent your whole book than any other part of it – a microscope held up to the significance of all the unsung heroes and unwritten stories lying there implicit in the text. As it’s obviously not just an indulgent little diversion, what inspired that and how do you see it fitting into the rest of it?

Thank you for appreciating that particular passage. As to what inspired it, it was mainly a contradiction inherent to the artistic process itself. There I was, writing a pirate story replete with cannons, cutlasses, and swashbuckling heroics, but the ugly truth is that maritime battles during the Golden Age of Piracy were gruesome affairs. Despite being a fictional story of visionary romance, I didn’t want to gloss over the truth of the history.

Each of those characters is living a story every bit as important as the stories that move our own lives.Besides, I have long noticed the expendability of background characters in our culture’s stories—the infamous “redshirt” characters from the original Star Trek television series, for example, the unnamed officers who were the first to die whenever a crew from the Starship Enterprise beamed down to an alien planet. Narratively, these deaths function to dramatize the peril that the main characters face, but doesn’t that seem shockingly cruel, to create cardboard characters devoid of all history and hope just to murder them? Doesn’t this, in fact, teach us to objectify everyone outside of the egotistical main character of our own life? In any event, if indeed the narrative required their death, I figured the least I could do was to regard the fact that each of those characters is living a story every bit as important as the stories that move our own lives. The hero’s journey lives within us all.

Actually, there were several similar moments as I progressed through the writing of this story. I would find myself at a culturally-familiar beat in the story, but as I felt into it, I realized that our stories actually misrepresent the realities of those moments. Our culture’s implicitly narcissistic stories would have you believe that when you triumph over another in conflict that you’ll be clinking smug champagne glasses as you dance on the bad guy’s grave. But if your soul is more sensitive than this socially-conditioned and dull-witted narcissism, what you’ll actually feel is grief and remorse that you ever stepped into a field of conflict in the first place.

That actually leads right into what I’d hoped to bring up next. The villain of your story is Goldtooth, a lipless buccaneer – both grotesque and pitiable. So what’s up with evil-looking evil people and hot heroes? (I’m aware that there may be possibly-karmic reasons to link this character’s disfigurement with another character’s vanity…)

Wasn’t it Glinda from The Wizard of Oz who informed Dorothy that “only bad witches are ugly?” While Gregory Maguire certainly endeavored to enhance our empathy for the Wicked Witch of the West in his bestselling novel, Wicked, you’re correct in observing that the conventional trope in storytelling is for evil people to look evil – if only as a shorthand means of leading the reader to disidentify with the villain. After all, Lord Voldemort from Harry Potter wasn’t particularly easy on the eyes, nor was Gollum from The Lord of the Rings. Anakin Skywalker’s hideous amputations and burns in Star Wars are yet another example, and the pattern is all the more true for his Sith overlords, the Emperor and, more recently, Supreme Leader Snoke. The list goes on.There is indeed something deeply monstrous about malignant narcissism, a fact we would do well to confront at this point in human history.

However, this is not necessarily what I had in mind with the pirate villain Goldtooth. After all, his counterpart in the modern-day side of the story—the gurusional sociopath Ivan—is strikingly handsome, along with his entire cult, the Holy Company of Beautiful People. And while karmic reincarnation is one interpretation of the relationship between the two storylines, it’s equally as likely that the pirate story is just a more visceral, archetypal expression of the modern-day story – who the characters would be once stripped of the masks of the modern world, or what Edgar Rice Burroughs called “the thin veneer of civilization.” In this case, there is indeed something deeply monstrous about malignant narcissism, a fact we would do well to confront at this point in human history.

Right on. In fact, I had an easier time empathizing with the disfigured Goldtooth than his maybe-future-incarnation Ivan. Funny how that “ugly villain” trope turned out to be a kind of prank. In any event, this book was such a treat, Tony. Thank you for talking with me about it.

Absolutely. Thank you for such an intriguing set of questions.

And may we be ever overwhelmed by how many people we love.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.